Lhotse, 8516 meters: Touching the void (by Javier Camacho)

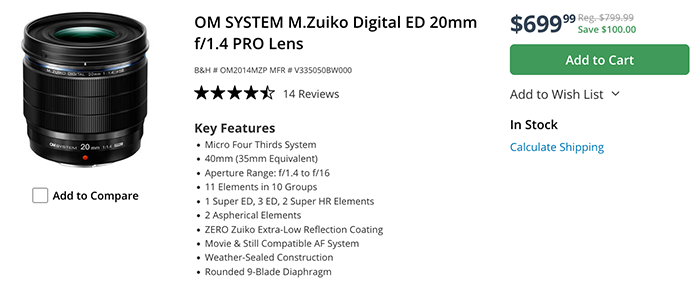

E-M5 Mark II • M.ZUIKO DIGITAL ED 7-14 mm 1:2.8 PRO • 1:2.8 • 1/25s • ISO 800

This is a guest post from Javier Camacho. The article was first posted on OlympusConsumer.com.

Lhotse, 8516 meters: Touching the void

by Javier Camacho

This story begins with a high degree of uncertainty. Having been unable to find anybody to join me on my journey to climb the fourth highest mountain in the world, I had to set off for the Himalayas on my own. In addition to this, I was about to confront the memories of the traumatic experience that I’d lived through just two years before at the base camp of the mountain. On that fateful day, 23 people lost their lives in an avalanche triggered by the earthquake that devastated Nepal in 2015.

In this bustling place, I was going to meet two old acquaintances of mine: Ferran Latorre, the Catalan mountaineer with whom I shared an expedition to Makalu, and Yannick Graziani, the French mountain guide with whom I had attempted to climb Broad Peak. I was going to be sharing the ascent route with them almost all the way to Camp 4, located at an altitude of 8,000 meters. They wanted to climb Mount Everest, and the route to Camp 4 is the same for both summits.

We quickly got going, and, in just four days, I set foot in the base camp, at an altitude of 5,400 meters. Memories of difficult times and images of the tragedy that I witnessed in 2015 entered my mind, but now the place looked as if nothing had happened. Meeting up with old friends, with whom I had many things to talk about, ensured that I quickly pushed those tragic memories aside.

I was feeling in peak physical condition, so I decided to rest for only a few days. I didn’t want to miss out on the opportunity to climb alongside my fellow base camp group members, Ferran and Yannick, who had spent quite a few days there and were more acclimatized.

With them and Austrian mountaineer Hans Wenzl, who had already conquered seven eight-thousanders, I braved the first day of the ascent. It was a very special day because I was going to discover the beauty of the treacherous Khumbu Icefall, of which I had seen so many photos and heard being discussed countless times.

Khumbu is much more awe-inspiring than anyone could ever imagine. Enormous blocks of ice form an infinite chaos, like giant dominoes ready to come tumbling down at any moment. It is a labyrinth of enormous, frozen crevasses. Walls of ice are overwhelmed with a stony silence that is only broken by the sound of ice cracking in its constant descent, or by the avalanches that every so often fall from the giant seracs that hang from neighboring Nuptse and the northwestern side of Mount Everest.

Little by little, we climbed this beautiful landscape, avoiding crevasses and ice walls, sometimes aided by the ladders that the “ice doctors” had placed. I cannot imagine a more difficult or dangerous job than that of these Sherpas, who are tasked with equipping and maintaining this stunning leg of the route.

E-M1 Mark II • M.ZUIKO DIGITAL ED 7-14 mm 1:2.8 PRO • 1:7.1 • 1/1250s • ISO 200

I was quite surprised at how physically well I was feeling, having barely acclimatised. I was able to keep up with the quick pace of my fellow group members, a necessity at these altitudes, and we promptly completed that stretch of the climb.

I had been looking forward to discovering the secrets of the Khumbu Icefall very much, but I was even more excited to see and photograph the stunning Valley of Silence.

It is, quite honestly, one of the most breathtaking places in the world. It is a vast landscape, filled with white giants that line the upward climb. In the background was our goal, Lhotse. To the left was Everest, the “Mother of the Universe.” To the right was the spectacular Nuptse.

In just four hours, we arrived at Camp 1, at an altitude of 6,050 meters. Here, I decided to break away from the group. I didn’t want to rush my acclimatization, so I chose to stay the night and join them the following day at Camp 2.

I didn’t want to acclimatize here. I thought about climbing to Pumori’s Camp 1 to sleep, skipping this perilous stopover. Camp 1 is very exposed to avalanches, especially those coming from neighboring Nuptse, but if I wanted to be able to keep up with my base camp group members, I had to do it.

The next morning, I left for Camp 2, covering a stretch of the route so beautiful that it took my breath away. It is no surprise to me that they call it the Valley of Silence, because anyone who discovers it, and more so when they explore it, is left speechless. It is a world of infinite ice and rock; a long valley, but one that is quick to cover, thanks to its gentle incline. At the end of the valley, the walls of Everest and Lhotse appear.

E-M1 Mark II • M.ZUIKO DIGITAL ED 7-14 mm 1:2.8 PRO • 1:7.1 • 1/1250s • ISO 200

In just over two hours, I was reunited with the group in the safety of Camp 2. Needless to say, the landscape is stunning. A huge wall of over 2,500 meters of blue ice separated us from the summits of Everest and Lhotse.

I rested there for one day; the same day that our group member Yannick took advantage of accompanying Ueli Steck, who was exploring Nuptse’s normal route. I took several photos of them. Little did I know that they would be the last. Swiss native Ueli Steck, the celebrated mountaineer who we saw that very night in our base camp, died a few hours later, having fallen from that mesmeric mountain.

That day, we reached Camp 3, at an altitude of 7,100 meters. It was hard to believe that just a few days earlier I had been in Spain. I had forced myself to acclimatize, but I felt so good that I wanted to join my fellow group members on their climb, to help me get accustomed to their pace. Access to this camp is via extraordinary ramps of blue ice that are as strong as steel. Both Everest and Lhotse seemed to be within reach, but there was still quite a way to go to reach the mountains. In fact, the mountains truly begin here. As we arrived at the camp, we received the news that an unidentified person had fallen from Nuptse, and that, given the height from which they fell, it was impossible that this person could have survived. We all instantly thought of Ueli, and a troubled and grief-stricken look etched itself onto Yannick’s face.

E-M1 Mark II • M.ZUIKO DIGITAL ED 12-40 mm 1:2.8 PRO • 1:8.0 • 1/800s • ISO 200

We stayed barely an hour at Camp 3, from where we quickly returned to the safety of Camp 2. There, our worst fears were confirmed. Ueli had died in the fall from the normal route to Nuptse.

The next day, we went straight down to base camp.

In just over a week, I had reached the 7,100-meter altitude of Camp 3 and I felt very strong, which made me feel very optimistic. However, an 8,000-meter mountain holds many surprises, and feeling well for a while means absolutely nothing.

After having rested for some days at the base camp due to bad weather, which caused many mountaineers to come down with the Khumbu cough, we carried on upwards. On this occasion, I skipped Camp 1 and went directly to Camp 2, which is much safer. We rested there for a few days, which helped to secure our acclimatization, and from there we proceeded to Camp 3. This time, we spent the night there.

I found this second climb to Camp 3 more difficult. I did not feel as well as I had felt on the first climb. On the way down, I started to feel quite unwell and, when I got to base camp, I was utterly exhausted. How could I have lost practically all my energy in such a short time? Doubt started to creep in. How was I going to climb 8,516 meters if I couldn’t even get down from Camp 3 to base camp? What’s more, my throat began to hurt, and I had an irritating cough. What consoled me was that the hard work was already done. I only had to wait for a window of good weather to try to reach the summit, as I had already completed my acclimatization.

Experience of past expeditions to 8,000-meter mountains told me not to be worried or lose faith in myself. Bad days will come, as will good days, and there was still a lot of the expedition ahead. There was no need to be disheartened. Eight thousand meters is a long journey, and the crucial days are those from Camp 3 upwards, which is where the mountain truly begins.

E-M1 Mark II • M.ZUIKO DIGITAL ED 12-40 mm 1:2.8 PRO • 1:8.0 • 1/1200s • ISO 200

Days went by and as they passed, we reached the first peaks, but only with the aid of artificial oxygen. At such altitudes, it is extremely cold and windy.

Not only did I not get better, but I got worse, despite having taken antibiotics. In the end, I made the tough decision to go down 1,000 meters to Pheriche, to help my body recuperate. At the 5,400-meter altitude of the base camp, I did not manage to overcome the illness that was gradually chipping away at my health and my spirit.

I spent two long days recovering, but when I tried to climb up to base camp again, my condition had only slightly improved and the coughing almost stopped me walking.

Be that as it may, after a short rest, I decided to join Hans, the Austrian, on his climb to Camp 2 to attempt to reach the summit as the weather forecast predicted that May 20 would be a summit day, with a window of good weather.

However, after a few hours climbing the Khumbu Icefall, I told Hans that I was going back. My cough was painful and persistent, and I wouldn’t be able to get anywhere with it, much less the summit of an 8,000-meter mountain. At that moment, I felt as if the mountain were slipping through my fingers.

I went back to take a second dose of antibiotics, and added to it a high dose of codeine. Ferran and Yannick went down to base camp after having spent a night at an 8,000-meter altitude on the South Col.

A little later, Hans arrived. He had been forced to abort his Everest climb due to the strong wind.

There we all were, reunited again. Meanwhile, the season was coming to an end. Many people abandoned the base camp, but we waited patiently for our moment. It had to come. Finally, various forecasts declared the twenty-seventh as a good summit day, with barely any wind.

The codeine did its job and my cough was slowly letting up, so on the twenty-second we all set off together. We went directly to Camp 2, where we rested for a day. I was feeling slightly weak due to the antibiotics, but I was excited and determined. This was going to be my last attempt, so I had to be in peak mental condition. There was no room for doubt.

E-M1 Mark II • M.ZUIKO DIGITAL ED 12-40 mm 1:2.8 PRO• 1:5.1 • 1/6400s • ISO 200

The climb to Camp 3 went quite well, but I didn’t sleep for very long that night because I was feeling quite nervous. From that point upwards, I would be entering the unknown. The mountain truly begins there, from the 7,100-meter mark upwards.

The climb to Camp 4 went as I’d expected. It was perhaps the most difficult day of the climb because it is very steep, and the gradient gave us no let-up whatsoever. The lack of oxygen was already incredibly noticeable, so I made the decision to get up really early and start the climb at 5:00 A.M., despite the extremely low temperatures.

The last hours were extremely difficult. The wind had picked up and a light flurry of snow started falling from around the Yellow Band.

Higher up, close to Camp 4, we reached a fork in the route. Everyone headed towards Everest, except me. After a few steep slopes, and in the midst of a strong blizzard, I reached what was left of Camp 4, a truly inhospitable place at an altitude of nearly 8,000 meters. I managed to get into a tent, the bottom half of which was suspended over the void. The tent was torn. It was on a forty-five-degree slope of ice and had quite a lot of snow inside, but I had to stay the night there, making sure not to move too much so as not to fall into the void.

E-M1 Mark II • M.ZUIKO DIGITAL ED 14-42 mm 1:3.5- 5.6 II R • 1:6.3 • 1/2000s • ISO 200

Gradually, the wind died down. It seemed that the next day the moment of truth would finally arrive. At midnight, I began my climb. The first few slopes were not very steep, and the stars were honorary witnesses to our climb. Little by little, we traversed the long corridor that would take us to the summit. The gradient increased. The route was in perfect condition. There was quite a lot of snow and neither the rock nor the ice could be seen. As we arrived at the steeper part, with a gradient of around seventy degrees, the sky started to cloud over and, little by little, the first snowflakes began to fall. Unbelievable. The weather forecast had failed us again. The weather ghosts of the summit days at Broad Peak and Manaslu had come back to haunt me, but I carried on regardless—although with increasing difficulty. A strong wind picked up, accompanied by a heavy snowfall. Every three steps necessitated a rest. It had already been a fair while since I had passed the 8,201 meters of Cho Oyu—the greatest altitude that I’d ever reached. I got the feeling that this corridor led directly to the heavens. The end would never be seen.

Visibility was low, and I only saw neighboring Everest a few times amid the blizzard.

Finally, I managed to see that a few hundred meters in front, the corridor opened up. In the center, the sharp point of the summit was visible.

Despite appearing so close, to me, it seemed never-ending. Every time I stopped to rest, I started to fall asleep. I even found myself dreaming while half-awake. I suppose this was the result of fatigue and barely having slept at all the previous two nights.

I was finding it increasingly more difficult to stay awake. I suspected that I was experiencing the onset of swelling on the brain, so, just in case, I took a dexamethasone. I wasn’t sure if I was dreaming or hallucinating. However, I couldn’t swallow it, because I instantly threw it up in a coughing fit.

If I wanted to get to the top, it was going to take all the energy and motivation that I could possibly muster. I had to fight to cover each centimeter that separated me from the summit. I had barely fifty meters left, and they seemed never-ending.

E-M1 Mark II • M.ZUIKO DIGITAL ED 12-40 mm 1:2.8 PRO • 1:6.3 • 1/1600s • ISO 200

Finally, after nine and a half hours of tough uphill climbing, I arrived at the summit. Barely one person could fit up there. On the other side of the sharp ridge, I sensed an incredibly deep abyss, but I did not manage to see further than a few meters, because the sky was completely covered, and the blizzard was intensifying. Thus, after five minutes at the summit and a few photographs, I decided to begin my descent quickly. This was not the day for rejoicing. The priority was to get down quickly.

For the first time in my life, I had a strange feeling at the summit of a mountain. Minimal joy. I didn’t even call my family. After so many gruelling and uncertain days, I was only concerned with getting to the bottom as soon as possible.

After a few moments, I began my descent, using the fixed rope that was keeping me alive. In a few hours, I arrived at Camp 4, where I retrieved the very few items that I had brought with me, and I continued my descent towards Camp 3. The way down has to be navigated very cautiously. Most accidents occur on the way down, due to fatigue and lack of concentration. One mistake can cost you everything.

My first thought was to get to Camp 3, but, in the end, despite the time and the fatigue, I made myself tea and went down to Camp 2. I arrived there at 9:30 P.M., completely exhausted and dehydrated after twenty-two hours of activity.

I started to feel safe there, but there was still a long and perilous journey left to reach the safety of base camp, once I’d passed the Khumbu Icefall. I arrived there the next day, worn out and still dehydrated, but happy to have reached the summit of Lhotse, reaching an altitude of 8,516 meters.

THANK YOU, OLYMPUS, FOR ACCOMPANYING ME ON MY JOURNEY TO THE HIGHEST HEIGHT WHILE I TOUCHED THE VOID.